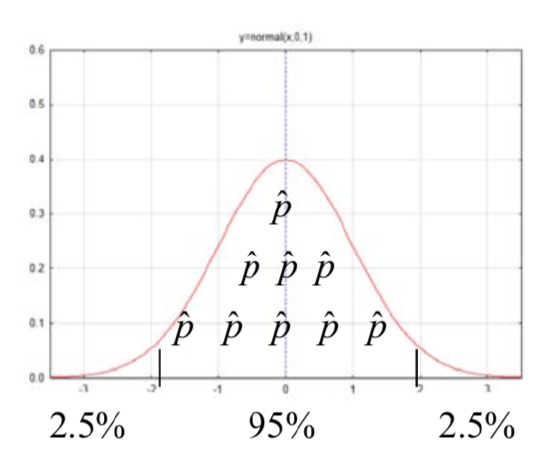

The inferences that were discussed in chapters 5 and 6 were based on the assumption of an a priori hypothesis that the researcher had about a population. However, there are times when the researchers do not have a hypothesis. In such cases they would simply like a good estimate of the parameter. By now you should realize that the statistic (which comes from the sample) will most likely not equal the parameter of the population, but it will be relatively close since it is part of the normally distributed collection of possible statistics. Consequently, the best that can be claimed is that the statistic is a point estimate of the parameter. Because half the statistics that could be selected are higher than the parameter and half are lower, and because the variation that can be expected for statistics is dependent, in part, upon sample size, then the knowledge of the statistic is insufficient for determining the degree to which it is a good estimate for the parameter. For this reason, estimates are provided with confidence intervals instead of point estimates. You are probably most familiar with the concept of confidence intervals from polling results preceding elections. A reporter might say that 48% of the people in a survey plan to vote for candidate A, with a margin of error of plus or minus 3%. The interpretation is that between 45% and 51% of the population of voters will vote for candidate A. The size of the margin of error provides information about the potential gap between the point estimate (statistic) and the parameter. The interval gives the range of values that is most likely to contain the true parameter. For a confidence interval of (0.45,0.51) the possibility exists that the candidate could have a majority of the support. The margin of error, and consequently the interval, is dependent upon the degree of confidence that is desired, the sample size, and the standard error of the sampling distribution. The logic behind the creation of confidence intervals can be demonstrated using the empirical rule, otherwise known as the 68-95-99.7 rule that you learned in Chapter 5. We know that of all the possible statistics that comprise a sampling distribution, 95% of them are within approximately 2 standard errors of the mean of the distribution. From this we can deduce that the mean of the distribution is within 2 standard errors of 95% of the possible statistics. By analogy, this is equivalent to saying that if you are less than two meters from the student who is seated next to you, then that student is less than two meters from you. Consequently, by taking the statistic and adding and subtracting two standard errors, an interval is created that should contain the parameter for 95% of the statistics we could get using a good random sampling process. When using the empirical rule, the number 2, in the phrase “2 standard errors”, is called a critical value. However, a good confidence interval requires a critical value with more precision than is provided by the empirical rule. Furthermore, there may be a desire to have the degree of confidence be something besides 95%. Common alternatives include 90% and 99% confidence intervals. If the degree of confidence is 95%, then the critical values separate the middle 95% of the possible statistics from the rest of the distribution. If the degree of confidence is 99%, then the critical values separate the middle 99% of the possible statistics from the rest of the distribution. Whether the critical value is found in the standard normal distribution (a \(z\) value) or in the t distributions (a t value) is based on the whether the confidence interval is for a proportion or a mean. The critical value and the standard error of the sampling distribution must be determined in order to calculate the margin of error. The critical value is found by first determining the area in one tail. The area in the left tail (AL) is found by subtracting the degree of confidence from 1 and then dividing this by 2. \[A_L = \dfrac>.\] For example, substituting into the formula for a 95% confidence interval produces \[A_L = \dfrac = 0.025\] The critical Z value for an area to the left of 0.025 is -1.96. Because of symmetry, the critical value of an area to the right of 0.025 is +1.96. This means that if we find the critical values corresponding to an area in the left tail of 0.025, that we will find the lines that separate the group of statistics with a 95% chance of being selected from the group that has a 5% chance of being selected.  An area in the left tail of 0.025, which is found in the body of the z distribution table, corresponds with a \(z^\) value of -1.96. This is shown in the section of the Z table shown below.

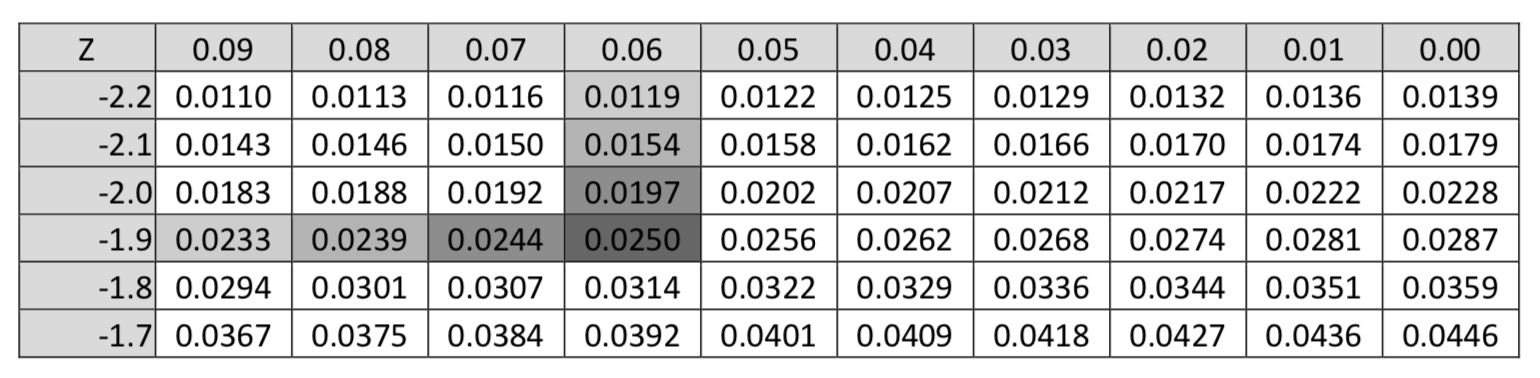

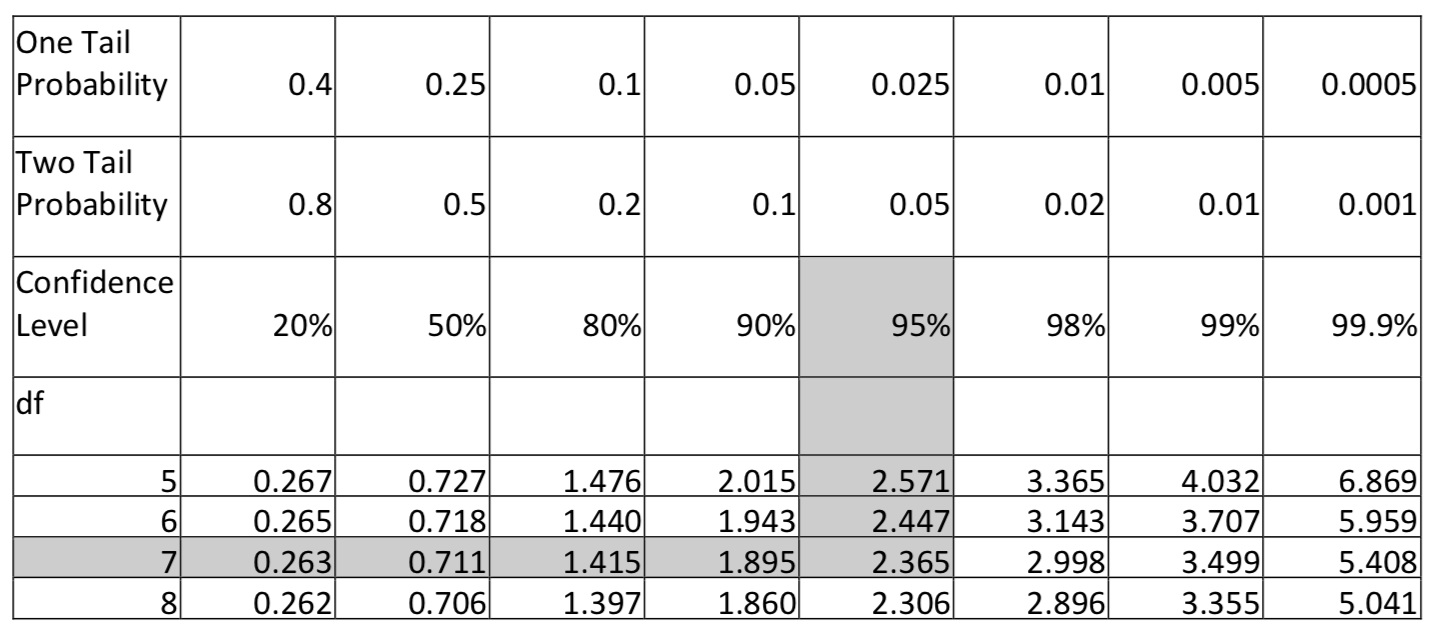

An area in the left tail of 0.025, which is found in the body of the z distribution table, corresponds with a \(z^\) value of -1.96. This is shown in the section of the Z table shown below.  The critical \(z\) value of -1.96 is also called the 2.5th percentile. That means that 2.5% of all possible statistics are below that value. Critical values can also be found using a TI 84 calculator. Use \(2^>\) Distr, #3 invnorm (percentile, \(\mu\), \(\sigma\)). For example invnorm(0.025,0,1) gives -1.95996 which rounds to -1.96. Confidence intervals for proportions always have a critical value found on the standard normal distribution. The \(z\) value that is found is given the notation \(z^\). These critical values vary based on the degree of confidence. The other most common confidence intervals are 90% and 99%. Complete the following table below to find these commonly used critical values.

The critical \(z\) value of -1.96 is also called the 2.5th percentile. That means that 2.5% of all possible statistics are below that value. Critical values can also be found using a TI 84 calculator. Use \(2^>\) Distr, #3 invnorm (percentile, \(\mu\), \(\sigma\)). For example invnorm(0.025,0,1) gives -1.95996 which rounds to -1.96. Confidence intervals for proportions always have a critical value found on the standard normal distribution. The \(z\) value that is found is given the notation \(z^\). These critical values vary based on the degree of confidence. The other most common confidence intervals are 90% and 99%. Complete the following table below to find these commonly used critical values.

| Degree of Confidence | Area in Left Tail | \(z^\) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.90 | ||

| 0.95 | 0.025 | 1.96 |

| 0.99 |

> = p\) and \(\mu_> = \mu\)). When testing hypotheses about the mean of the distribution, we assume these values because we assume the null hypothesis is true. However, when creating confidence intervals, we admit to not knowing these values and so consequently we cannot use the standard error. For example, the standard error for the \(\sigma_<\hat

> = \sqrt<\dfrac \) is used to estimate \(p\) and \(s\) is used to estimate \(\sigma\). The estimated standard errors then become: \(s_<\hat > = \sqrt<\dfrac<\hat (1 - \hat )>>\) and \(s_> = \dfrac<\sqrt>\). The groundwork has now been laid to develop the confidence interval formulas for the situations for which we tested hypotheses in the preceding chapter, namely \(p\), \(p_A - p_B\), \(\mu\), and \(\mu_A - \mu_B\). The table below summarizes these four parameters, their distributions and estimated standard errors. > = \sqrt<\dfrac<\hat (1 - \hat )>>\) _B> = \sqrt<\dfrac<\hat _A(1 - \hat _A)> + \dfrac<\hat _B(1 - \hat _B)>>\)

Parameter Distribution Estimated Standard Error Proportion for one population, \(p\)

\(s_<\hat Difference between proportions for two populations, \(p_A - p_B\)

\(s__A - \bar M ean for one population or mean difference for dependent data, \(\mu\)

\(s_> = \dfrac<\sqrt>\) D ifference between means of two independent populations, \(\mu_A - \mu_B\)

\(s__A - \bar_B> = \sqrt<[\dfrac<(n_A - 1) s_^ + (n_B - 1) s_^>][\dfrac + \dfrac]>\)

Notice that all the confidence intervals have the same format, even though some look more difficult than others.

statistic \(\pm\) margin of error

statistic \(\pm\) critical value \(\times\) estimated standard error

Confidence intervals about the proportion for one population:

Confidence intervals for the difference in proportions between two populations:

Remember that \(q = 1 – p\).

Confidence intervals for the mean for one population:

Confidence interval for the difference between two independent mean: